The first definition for the word conservative from Dictionary.com reads as follows: “disposed to preserve existing conditions, institutions, etc., or to restore traditional ones, and to limit change.” With this definition in mind, it comes as no surprise to me that those who identify themselves as politically conservative often employ the appeal to antiquity, which is a common logical fallacy. When you are averse to change, it makes sense to argue that things should stay the same because “that’s the way they’ve always been.” That argument, in a nutshell, is the appeal to antiquity.

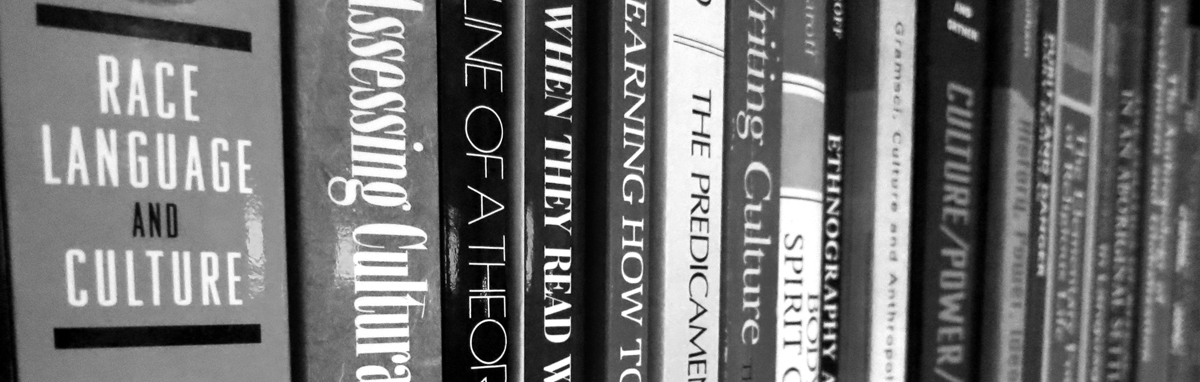

The appeal to antiquity is part of a family of fallacies known as “irrelevant appeals.” The idea is that because something has been done or believed for a long time, it must be true. Obviously we know that this is not the case; people used to believe that the earth was flat; that all disease was caused by “bad air”; and that phrenology was an accurate science. I know that political conservatives aren’t the only people to employ this fallacy, but I do tend to associate it with common conservative arguments about a variety of hot political topics. For example, an extremely common argument against legalizing gay marriage is that marriage has always been defined as a union between one man and one woman. Aside from the fact that this is not historically accurate, it clearly employs the appeal to antiquity: that’s the way things have always been; therefore, we shouldn’t change anything.

The opposite of the appeal to antiquity is the appeal to novelty. This fallacy holds that because something is newer it must be better, but that’s just as wrong as the appeal to antiquity. New discoveries are made about things all the time that ultimately turn out not to be true. This is related to the bandwagon fallacy, which proposes that if a bunch of people believe in a new idea it must be true. This holds for recent research into all sorts of things that may be good or bad for us, such as the potential benefits of various dietary supplements. Recent research into the benefits of taking multivitamins has concluded that they do not appear to benefit human health. This may well be true, but it is not the recency of the conclusion that makes it so; and I wouldn’t be surprised if further research disputes this claim. (This topic deserves a rant of its own discussing the rampant fallacies that are employed by consumers of mainstream media reporting on scientific research – both the way the information is presented and the way it is interpreted leaves much to be desired.)

Back to the appeal to antiquity. Just like the appeal to novelty, the age of the topic under consideration is of no relevance to its veracity. Again, the position being argued may well be true, but it is not its age that makes it so. And conversely, because something is old does not mean it should automatically be abandoned. The point is that the age of a topic under discussion has no relevance to its validity. So, to use a few more examples, just because something is written into old documents that set up the governance of our nation does not mean they remain ideas that should be embraced. For example, should Black Americans still be considered 3/5ths of a person? Should we still allow slavery? Should women still not be allowed to vote? Should Native Americans not be granted US citizenship? And for a very hot topic in our current culture wars… should every American citizen be allowed to own a gun just because that’s always been a part of our governing tradition? Don’t mistake me – there are valid arguments for and against gun ownership, but the appeal to antiquity is not one of them. And as an example of a governing novelty that did not work out: should alcohol still be prohibited? Prohibition did not work – its newness as an amendment to the US Constitution did not make it a success.

So, if you are going to argue that something should remain as it is, do not make the mistake of deploying the appeal to antiquity. There are many good arguments in support of a variety of positions on our many cultural conflicts, but saying “that’s the way it’s always been” is not one of them. The more carefully you select your arguments, the more likely you are to be heard.