Rat poison saved my life. I know how strange that sounds, but it’s true. In July 2003 I was hospitalized with a pulmonary embolism – a blood clot in my lung. The treatment is blood thinners – IV heparin while in the hospital for a week, then oral warfarin – brand name Coumadin – for six months afterwards to keep dissolving the clot and to prevent a recurrence. Warfarin is an anti-coagulant, and it happens to be very effective as a rodenticide by causing fatal internal bleeding in rats that ingest it in the form of poison baits. So what’s the takeaway? It’s really quite simple: the dose makes the poison.

I bring this up because I have noticed that it doesn’t take much to frighten people by telling them about “disgusting” or “scary” or “poisonous” stuff that shows up in food. This absolutely, positively requires a great deal of skepticism and critical thinking. Case in point: I ran across an article in the Huffington Post that capitalizes directly on this sort of fear-mongering. Titled “9 Disgusting Things You Didn’t Know You’ve Been Eating Your Whole Life,” the article runs through a list of food additives that are apparently supposed to make us feel like the food industry is bent on poisoning its customers. Now, I’m not stupid; I’m well aware that there is all sorts of stuff in our food that is not exactly healthy, and even some stuff that could be dangerous. I am concerned about modern eating habits (my own included!) and think it’s rather frightening how removed we are from the process of providing food for millions of people. In fact, when I teach the section on subsistence in my cultural anthropology classes, I ask my students to think about what they would eat if the world as we know it came to an end. Do they have the remotest inkling of what they would eat if there were no grocery stores or restaurants? And even if they talk about hunting, I ask them, when the bullets run out, how will you kill animals? Do you know how to prepare them? How will you keep that food from spoiling? What plant foods will you eat? I have no doubt that when the shit hits the fan for humanity, those few cultural groups that still forage or practice horticulture and pastoralism will be the only survivors, with a few exceptions for those who have learned skills for living off the land in nations like the United States (although even these few won’t survive as long-term populations unless they meet other people and are able to form larger groups that can sustain population growth).

So what does any of this have to do with the HuffPo article? My real point is that people get unreasonably frightened or disgusted by things without thinking through why they are frightened or disgusted. The first thing on the list in the article is castoreum. This is a substance that is produced in the anal sacs of beavers, and even I have to admit that it sounds pretty disgusting. It is used as a flavoring similar to vanilla, although according to Wikipedia the food industry in the US only uses about 300 pounds of it a year. My problem with this is the automatic reaction that some parts of the animal are not acceptable for food use and others are. The way we use animal parts is culturally determined and completely arbitrary. Why is castoreum any more disgusting than drinking the liquid that shoots out of a cow teat? Some people eat tongue – why is that body part any worse than eating the ground up flesh from a pig’s side? What about eggs, which are essentially the menstrual flow of a chicken contained in a shell? Disgust, again, is culturally determined and therefore ultimately arbitrary from an objective standpoint.

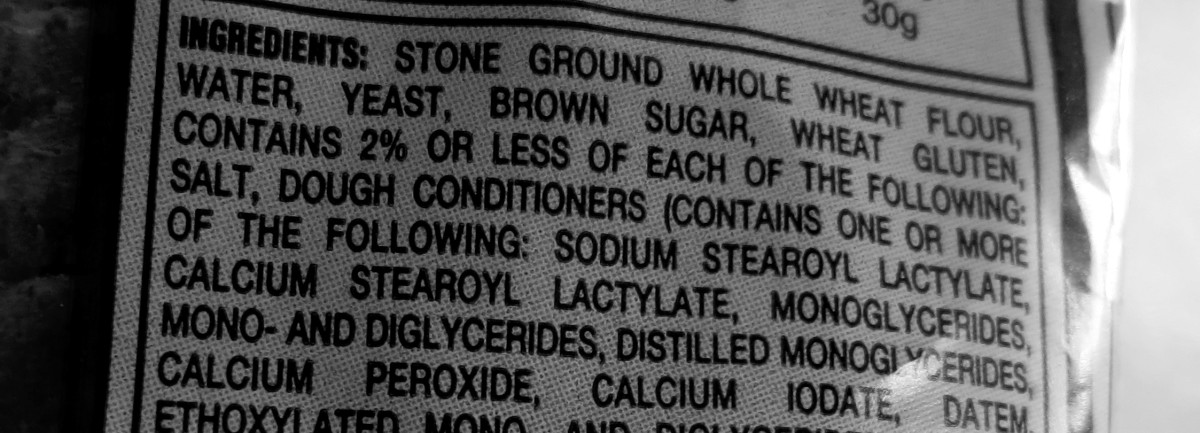

Other things listed in the article include L-cysteine, which is one of the amino acids that is found in human hair; sand; coal tar; anti-freeze; and a few others. The human hair bit is similar to the beaver anal secretions bit – we just knee-jerk find it disgusting, but it’s not as if there is actual human hair in your food! Every single living thing is made of amino acids, so you could make the argument that any food that contains an amino acid is part, I don’t know, semen? Bile? Blood? In other words, without the full background of the chemical all you read is that human hair has a component that is processed into a food additive and the implication is that you are directly consuming hair. As for the things like anti-freeze and coal tar, reference back to the dose making the poison. Once again, it’s not like food companies are pouring Prestone into your food. The ingredient in question is called propylene glycol, which has many of the same properties as ethylene glycol, which is what is actually used in automobile antifreeze. Propylene glycol is not only used in food but in medications that are not soluble in water – so much like warfarin, propylene glycol in the right dose and formulation has important medical applications.

I could go through the list one by one, but I’m hoping that these examples make my point that so much information and context is left out of articles like this. I really don’t understand the desire to frighten and disgust people by only focusing on shock value rather than useful information. Again, I want to stress that I realize there are bad things in our food, and I am firmly committed to the idea that most companies are more concerned about their bottom line than they are about the health and safety of consumers; but it’s also important to remember that if companies sicken or kill their customers they won’t be in business for long! And I know that plenty of people automatically distrust government agencies like the FDA, but again, what does the FDA gain by allowing truly dangerous chemicals to be part of the food supply? It behooves us to think very carefully about this sort of thing.

A final point: in reading the comments at the end of the HuffPo article, I was amazed at the self-righteousness and privilege of many of the contributors. So many bragged about only eating fresh food from the farmers’ market or making their own bread or only buying organically raised meat or making baby food from scratch or blah blah blah. Have these people ever been outside their privileged little bubble and considered how the real world works for so many people? Farmers’ markets are great – if there’s one in your neighborhood and you can afford to pay the premium prices. Organic meat? Only if there is a fancy grocery store nearby and you want to pay double the price. Food made from scratch? Sure, if you have the time and the tools and the money for the often pricey ingredients. It’s terrific that a lot of people are trying to get back to basics with food prep – I myself make bread from scratch – but it fails to recognize the deep inequality and lack of access to resources that so many people in the United States, and the world, have to contend with – but that’s a rant for another time.