When I was six years old, a neighborhood boy promised me that he would “show me his” if I “showed him mine.” That seemed like a fair deal to me. He told me to wait in his closet, which my six-year-old mind didn’t question, and when the door opened a few minutes later, several boys from the neighborhood had gathered in his room. I was scared, but I “showed them mine.” I didn’t get to see theirs. When I was in junior high, a fellow student threatened to rape me during a sleepover, and chased me into a bathroom where I locked myself in while he pounded on the door. When I was in college, a car full of men at a stoplight motioned to me to roll down my window, and when I did, they asked me if I gave good head. Also in college, I experienced two separate incidents with two different men where I engaged in a consensual kiss, and a few minutes later had a penis being forced into my mouth. In both incidents, I was alarmed, but followed through with the sexual activity because it seemed more dangerous to stop… and because I was embarrassed. As a woman in my late twenties, I had sex with a man I didn’t want to have sex with, again because it seemed more dangerous – and embarrassing – to tell him no. As a working adult, I endured a supervisor who peppered nearly every interaction with deeply sexual remarks and innuendoes. I told myself I was ok with it because he didn’t really mean it, he did it to a lot of women, not just me… and because I needed my job and had no confidence that anything would be done about his behavior if I reported it.

The torrent of sexual harassment, abuse, and assault allegations that is currently sweeping through the nation is making me simultaneously angry (on behalf of the women), sad (same), and uneasy. Why uneasy? Because we seem to be experiencing a pendulum swing during which any behavior by a man that can possibly be interpreted as inappropriate is being called assault;* and more so because behavior that actually IS assault is being denied, brushed off, or treated as a deliberate lie or conspiracy. This is a dangerous dichotomy. The pendulum will eventually return to center, but when it does, I hope it is with a new calibration. To be perfectly clear: I believe the women (and men, in some cases) who have come forward. I also believe that any unwanted touching, words, innuendoes, actions, etc. is inappropriate at best, and truly constitutes assault at worst. Luckily, I don’t feel permanently scarred or damaged by any of the incidents I went through, but I understand why some victims carry lifelong feelings of fear and shame.

This moment of reckoning had gotten me thinking again about something I have often wondered: why do human males engage in this sort of behavior? How much is nature, and how much is nurture? Broadly, it is easy to answer this question very quickly: it is both. But again, I need to make myself completely clear: the nature/biological component of this behavior does not excuse it. And, at the same time, the nurture/cultural component of this behavior shares much of the blame.

Humans are primates – specifically, we are one of the great apes (along with orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, and bonobos) . Our closest living relative is the chimpanzee. Chimps have active sex lives that are also linked to their social lives and to the status of individuals within the group. Now, our close genetic relationship with chimps does not destine us to behave in the same ways, but it gives us some insight into the biological underpinnings of some aspects of our behavior. Broadly, the point of sex is reproduction; and when you look at reproduction through a biological, evolutionary lens, it provides a set of explanatory principles for mating behaviors. Does this apply to humans too? Of course. Another caution about making myself perfectly clear: sexual behavior as an evolutionary strategy does not excuse sexual harassment, abuse, or assault. Nor does it provide a full explanatory mechanism for the ways in which humans engage in reproductive behavior. We are unique among animals in that we have learned how to have intercourse purely for pleasure – we invented birth control, and have found ways to have sex without reproducing. That means sex, for humans, is as much social as it is biological. But that doesn’t remove the biological underpinnings. The sex drive is still about the possibility of reproduction, but in humans, as in chimps, it is also linked to status; and in humans, status is the same thing as power. Here’s where we get the terrible overlap between sex as biology and sex as culture: men who engage in sexually abusive behavior are motivated by lust for power just as much as lust for physical gratification.

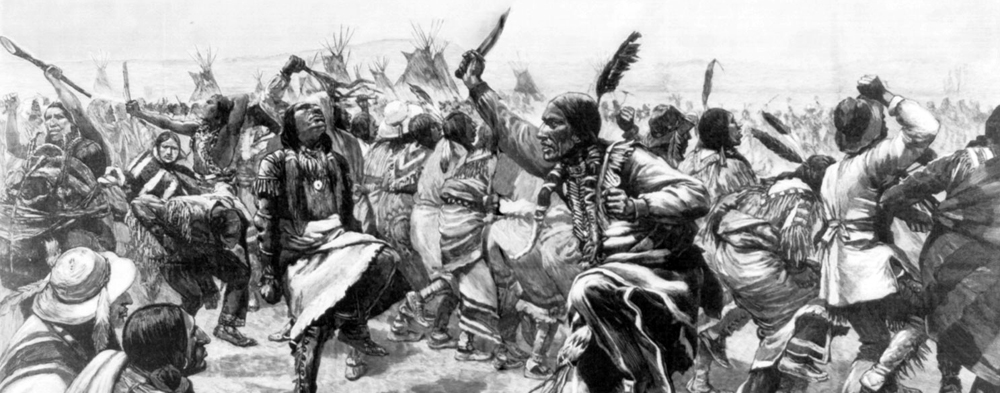

During episodes of war or conflict, men are often reported to rape captive enemy women. Again, very broadly, this is about power, status, and the dehumanization of the enemy. Nature or nurture? Powerful men are now being accused of treating women (or in the case of Kevin Spacey, men) as objects of sexual gratification, rather than as human beings – similar to the men who rape captive enemy women, even if their behavior does not (always) rise to the level of rape. Nature or nurture?

I am not a sociobiologist, but I believe it is a mistake to dismiss or ignore the biological underpinnings of human behavior. BUT, and this is a hugely important but: unlike other animals, humans have culture. We have nurture. We have the ability to teach people right from wrong. So why are men still assaulting, abusing, and harassing women? Because they’ve learned they can get away with it. It’s nurture, not nature, that lets down the victims. It’s nurture, not nature, that says “Boys will be boys.” It’s nurture, not nature, that says “It’s just locker-room talk.” It’s nurture, not nature, that says “Who will believe the intern over the Congressman?” It’s nurture, not nature, that says “men can’t control themselves” and that women should “take it as a compliment.” And now it’s nurture, not nature, that is saying WE HAVE HAD ENOUGH. It’s nurture, not nature, that has to teach our boys and girls about respect, equality, and consent. It’s nurture, not nature, that has to battle the perpetuation of toxic masculinity. It’s nurture, not nature, that has to point to the past and say it was wrong then and it’s wrong now. Let the pendulum continue to swing, and when it comes to rest, maybe, finally, this time, nurture will have taught men that they’ve gotten away with it for the last time.

*This is a topic to cover at another time, but briefly, I do think that we need to have a discussion about how to define and approach actions that are inappropriate but do not rise to the level of harassment, abuse, or assault. And that said, we need to work on reducing inappropriate behavior too, but in a way that is educational rather than accusatory. I believe that elevating the merely inappropriate to the realm of assault can serve to minimize actions that truly rise to that definition.