In my last post, I wrote about tolerance of other people’s beliefs. I want to continue that line of thought but focus this time on tolerance of other people’s appearance. I have gotten into the habit of calling myself on my initial, gut reactions to how people look. It’s a sad truth that people react immediately and viscerally to how others appear, and will form a snap judgement of that person based on what they see. That initial judgement may not last, but it is always there, and we seldom, if ever, pause to unpack the unconscious, culturally dictated assumptions that undergird our reactions. In anthropology, we call this ascribed status.

Ascribed status is technically defined as a status that one cannot help possessing, like gender, race, or age. It is something we cannot change. This contrasts with achieved status, which is, as the name makes clear, a status you can achieve. This can be good – earning a degree – or bad – earning a criminal record. Ascribing status is exactly what we do when we unconsciously size somebody up just by looking at them. The problem is, the status we may ascribe to someone may not be a status they actually have. Some stuff seems so obvious – of course that person is male, obviously that person is Black – but we often make mistakes. How many of us have been mistakenly ascribed with the wrong racial or ethnic category, the wrong age, even the wrong gender? When I was a student at Humboldt State, many people assumed I was a lesbian because I had short hair and wore nothing but hiking boots, jeans, and flannel shirts! This kind of automatic ascription becomes quite problematic when you add in all the assumptions and stereotypes that accompany it. So, for example, if you see a dark-skinned person, you ascribe to them the race of Black, which in turn may make you come to some other conclusions about this person – for example, that the person is socioeconomically disadvantaged, likely uneducated, probably criminal, and potentially dangerous. Now, I am very deliberately choosing inflammatory examples, but the reality of the way our society enculturates us means that stereotypes – especially negative ones – can be very deeply imbedded. Even if we don’t consciously realize or acknowledge our reactions (and I think many of us don’t), they are there. It doesn’t mean we act on those reactions, but we have them nonetheless. We make similar assumptions based on a person’s assumed gender, age, and many other aspects of their physical appearance. In fact, I think it might be more accurate to rename ascribed status to assumed status.

We have come to a place in our culture and society where we have been taught that certain ascribed aspects of a person should not be subjected to assumptions and stereotypes. For example, we are not supposed to judge a person for their race or gender. Yes, racism and sexism still exist, for certain, but people are now routinely called out when they engage in racist and sexist behavior. It is not socially acceptable to make racial jokes or use racial epithets, and it is illegal to discriminate based on race (or gender, sexual orientation, age, disability, etc.). The same is becoming more and more true of disability and sexual orientation as well. Yet if we are honest with ourselves, I think we should all – and I mean ALL – admit that we still harbor unconscious reactions to people that, if we make ourselves aware of them, should probably cause us to feel embarrassed or ashamed of ourselves. I know that when I see someone and have an automatic reaction, if I stop to examine my reaction I am often surprised at the stereotypical assumptions I will still, unconsciously, make.

As always, I believe there are important evolutionary underpinnings to this type of reaction. I’ve said before that humans are pattern-seeking animals. It is beneficial to categorize situations that might be harmful or threatening so that we can recognize them if they occur again. Both individual and group survival are enhanced if people learn to recognize and avoid danger. This extends from things as simple as avoiding poisonous plants and dangerous animals to things as complex as learning how to speak and interact with others in social situations. As animals we are always striving to keep ourselves out of trouble. As humans, we recognize that trouble can easily be caused by other humans. Unfortunately our pattern-seeking propensities can lead to mistakes, where we see patterns where no pattern actually exists, or where a situation may be perceived as more threatening than it actually is. This is a nutshell version of how stereotypes are formed: we see an apparent pattern of behavior by a few people, and based on their appearance, group membership, culture, or any number of other characteristics, we ascribe those behaviors to every perceived member of that group. Thus, some Black people are criminals; therefore all Black people are criminals. Of course, none of this stereotyping takes account of the myriad and complex cultural and institutional systems that contribute to the stereotyped behavior in the first place; that’s too nuanced for a pattern-seeking reaction that evolved in a paleolithic time when other groups of humans could, indeed, be extremely dangerous to your own group’s survival. In that time, better safe than sorry could have mean the difference between life and death, so it’s better to mistakenly think a safe thing is dangerous than the other way around.

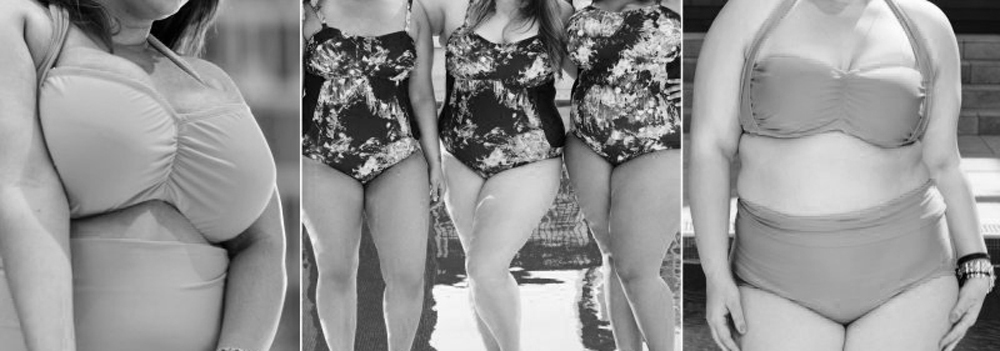

This is all a long introduction to my real topic: the ascribed statuses that come along with people’s bodies. We aren’t just concerned with skin color, age, or gender – we are concerned with overall appearance. What characteristics do you ascribe to a fat person? What is your visceral reaction when you see an overweight person in public? Is it a kind one? I doubt it. What about when someone is skeletally thin? How about if they have funny hair, or unfashionable clothes, or a bunch of piercings and tattoos? What are your assumptions? I think that physical appearance is one of the last things it is still acceptable to ridicule publicly – especially when it comes to people of size. That is why I titled this rant “Bikini Bodies.” We have assumptions about who should be allowed to wear a bikini in public. We roll our eyes and complain about being visually assaulted by an obese person who dares to wear spandex. There are websites dedicated to ridiculing people for what they wear or how they look (I won’t link to any because I refuse to support them, although in the interest of full disclosure I will admit to having visited them in the past – and I did it purely for the entertainment value, before I started to examine my own reactions). We get a guilty, schadenfreude-inflected pleasure from celebrity paparazzi photos that reveal cellulite, wrinkles, and stretch marks. We insult and criticize when a celebrity – especially a female – is too thin, or too Photoshopped, or too made up. Why have we learned that it’s not acceptable to criticize a person’s race, gender, etc. but it’s still okay to assume that because a person is fat or fashion-challenged, they are somehow morally suspect? These are other human beings. Why is it so easy to forget that? They love and are loved by other human beings. They have feelings, lives, experiences, worlds we know nothing about, but to us they are just a symbol of things we’d rather avoid.

Some of the people I love most in this world are fat. I’m sure some of the people my readers love most in this world are fat. We turn to attribution error to tell ourselves that for our loved ones, it’s different – they aren’t lazy or lacking in will power, and they aren’t moral failures – they are good people who just let eating get the better of them. But for the rest of the overweight, it’s a different story – it is their fault they are fat, and we judge them because of it. I don’t write this to shame anyone. I write it because it’s time for us to examine our ascriptions and change our assumptions. It’s time for us to recognize that body stereotyping – and the real, documented discrimination that comes with it – is just as bad as other forms of stereotyping. It’s time for us to put down the magazines that tell us “How to Get a Bikini Body!” You want to know how to get a bikini body? Put a bikini on your body – and wear it proudly and without shame.