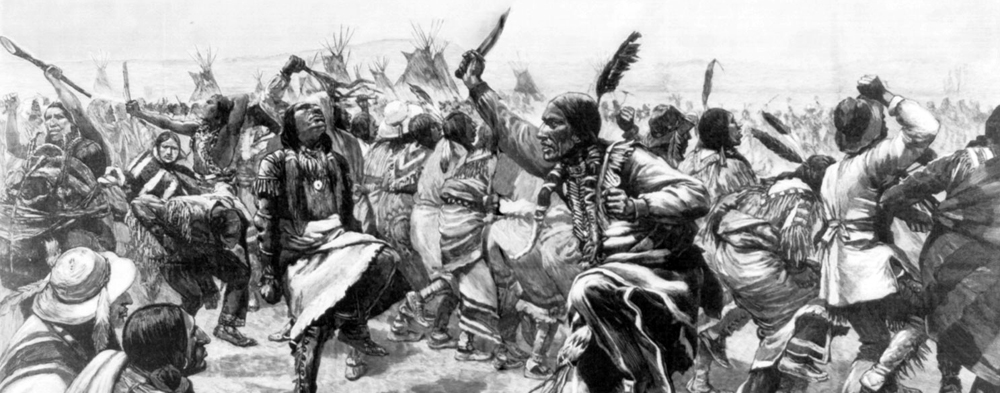

Around 1870, when colonization of the western United States by Europeans and their descendants was reaching its zenith, a movement that came to be known as the Ghost Dance began appearing in Native American communities. Taught by a Paiute spiritual leader named Wokova, the Ghost Dance was a ritual meant to cleanse the spirit, promote clean living, and reunite the living with the spirits of the dead. With the help of these spirits, the living would ultimately drive the white usurpers from the land; bring back the buffalo; usher in a time of peace, prosperity, happiness, and unity; and restore the ways of life that had been crushed by colonialism. As the Ghost Dance spread, it changed somewhat in form depending on the culture that adopted it; amongst the Lakota, it invoked the promise of a total transformation of society. Perceiving the Lakota’s wish for a new and better world as a threat, in 1890 the United States Army slaughtered at least 153 Lakota at Wounded Knee in South Dakota. Over time, the Ghost Dance slowly petered out, and although it is still practiced by a few tribes today, it is no longer with the expectation that adherence to the dance and its teachings will usher in a new era.

Phenomena like the Ghost Dance are a part of what anthropologists call revitalization movements. Similar to millenarianism, revitalization movements generally spring up in times of extreme social unrest, such as colonialism, war, or government oppression of citizens or social groups. The purpose of the movement is to usher in a new type of society; restore social values that have been repressed or denied; or return life to the way it “used to be.” They generally involve a ritual component and special rules that are adhered to by the followers, and can sometimes manifest as cults. A modern example is the Heaven’s Gate cult, in which the followers believed that a spaceship was concealed in the tail of the Hale-Bopp comet and was coming to pick them up to take them to a better life away from Earth on a heaven-like planet. Unfortunately, validating your ticket to board this heavenly ship meant forsaking your life on Earth – via suicide. In 1997, 38 cult members dosed themselves with phenobarbitol, applesauce, and vodka, and left this earthly plane. I’m going to go ahead and assume that they did NOT make it to heaven’s gate.

Sometimes revitalization movements are successful. There’s an excellent argument that Christianity began as a revitalization movement. Unhappy with Roman rule, many citizens throughout the Roman empire looked to prophets who promised a better life; Jesus of Nazareth was just one of those prophets, but he turned out to be one of the few with tremendous staying power. He promised that by following his teachings, a better life could be had – both in this life AND in the next one. In fact, that is the trick of Christianity’s longevity: unlike the Ghost Dance, which promised change in this life, Jesus promised the ultimate reward in the heavenly afterlife. Why is that important? Because unlike the Ghost Dance, where people eventually began to realize that the change they sought was not coming, no one has returned from heaven to either refute or verify Jesus’ teachings – therefore, people can keep believing because there’s no one around to say otherwise. (I realize this is a gross oversimplification of Christianity overall, but I believe it is key to why it is still around after 2,000+ years; and the same is true for all religions that promise rewards after this life or in the next one.) What of more recent religions like Mormonism and Scientology, or even New Age spiritualism? I think there are at least some aspects of revitalization movements in all of them.

I’ve been thinking a lot about revitalization movements recently, because I think it provides a basis for analyzing not just recent religious movements and cults but the sometimes hysterical and irrational adherence of people to their particular political ideologies. We are living in a time, believe it or not, that is actually safer and more peaceful than any other time in history (an idea explained in great detail by many authors, but to great effect by both Steven Pinker’s book The Better Angels of Our Nature and Michael Shermer’s bookThe Moral Arc). BUT (and it’s a big but): people feel less safe. We feel threatened by conflict and violence. We fear the loss of our most cherished values. We see economic inequality, a loss of stability, a lack of trust, an increase in terrorism, a deepening of racial and cultural divides, greater political differences, more apathy, more protesting, more rioting, more destruction, more fear… In short, we see the things that the Indians saw during colonialism and that the Jews saw under the Romans. So it comes as no surprise to me that, in this election season, some people’s adherence to their candidate’s values has taken on the quality of a revitalization movement. And I admit that I’m a partisan, but I feel that this is more evident amongst conservatives – and particularly among Donald Trump’s supporters. Without doubt, it also exists amongst the die-hard Bernie Sanders supporters, or the third-party supporters of Jill Stein (Green) and Gary Johnson (Libertarian), but it seems to have reached a fever pitch on the far right of the Republican party. And it makes sense: the very dictionary definition of conservative is “disposed to preserve existing conditions, institutions, etc., or to restore traditional ones, and to limit change.” And is that not exactly what Trump is proposing with his slogan, “Make America Great Again“? The Ghost Dance movement sought the same thing: a return to previous conditions.

I believe the revitalization movement concept also applies to terrorist groups such as ISIS (see here for other names for the group; some have started using the term Da’esh or Daesh specifically because ISIS doesn’t like it). Clearly, ISIS wants to see a different kind of world and intends to usher it in not through a dance or by committing suicide and boarding a spacecraft, but by terrorizing the world into accepting their extreme interpretation of Islam (one which, I am compelled to note, is not shared by the vast majority of Muslims). ISIS adherents tend to be disillusioned young men who feel ignored or unappreciated by their families, friends, and/or cultures, so they are easily drawn in to ISIS’ promise of a new and better life. I can’t think of a much better description of a revitalization movement.

So why all these revitalization movements now? Some of these ideas deserve posts of their own, but in general, I think there are a few things at play. For one, human groups tend to operate at maximum efficiency with maximum communal cooperation at the hunter-gatherer level, when everybody knows everybody else, and the survival of the group and the individual are inextricably intertwined (I wrote more about this idea, and the overall concept of cultural collapse, here). With global population fast approaching 7.5 billion people, the hunter-gatherer model is all but extinct (there are still foraging groups, but they are heavily influenced by the modernized world in which they live). Plus, as noted above, people are living in fear, and it’s a fear that I think is massively exacerbated by the internet and social media and the ease of global information exchange we now have. We hear about everything that happens now, good and bad, which leads to the mistaken assumption that bad things happen more than they actually do. Finally (and trust me, this paragraph is not meant to be exhaustive of all the potential causes of revitalization-movement-like behavior), we are living at a time of economic and social inequality that has not been seen for generations. Many, if not most, historical revitalization movements have arisen in similar times. Put all this together, and we have no reason to be surprised that it’s happening again.